When one thinks of an archive, they likely imagine a set of photographs or slides, reams upon reams of paper, boxes, records, and perhaps a catalog. It is likely to consist of objects that contain information regarding a specific moment in history, a cultural movement, or a catastrophic event. They imagine it is probably housed in an institution of some kind, a library or a museum, which has the resources to gather and maintain a collection.

Archives are generally thought of as collections that inform us about the past. They allow us to view the past from the present, to consider the materials of a time and place as evidence of the contours of its reality. As much as we might like them to, archives can never contain a complete past. We can never know, for example, all of the details of the lives of each person that appears unnamed, or as one among statistics on a page.

Writer and academic Saidiya Hartman delves into the violence inherent in archives in her seminal essay Venus in Two Acts, about the recurring mention of Venus, or the Sable Venus, as a stand-in for the many anonymous women that appear in the archives of Atlantic slavery.

The archives that we have hold the stories of slaveholders, sailors, and traders, but not one autobiographical narrative of a female captive who survived. “The loss of stories sharpens the hunger for them,” Hartman writes. “[I]n these circumstances, it would not be far-fetched to consider stories as a form of compensation or even as reparations, perhaps the only kind we will ever receive.”

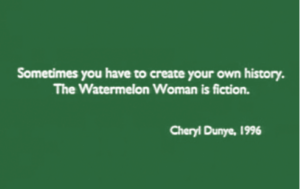

In 1996, Liberian-American director and producer Cheryl Dunye released and starred in her first feature-length film, The Watermelon Woman, which is arguably a film about such stories. It became an instant classic in queer cinema, as the first US feature-length narrative film written and directed by an out Black lesbian about Black lesbians.

Cheryl Dunye appearing as Cheryl in the film The Watermelon Woman.

In the film Dunye, who stars as the main character, also named Cheryl, is a young Black lesbian woman working in a video store in Philadelphia in the 90’s (for the sake of clarity, the director will be called Dunye while the character she plays in the film will be called Cheryl.) She works there with her friend Tamara, played by Valarie Walker. Cheryl begins taking films from the 1930’s and 40’s home to watch, and notes that many of the Black actresses are named in the credits only by their roles. One actress in particular draws her attention, a woman credited as “The Watermelon Woman.” Cheryl convinces Tamara to join her on a quest to find out everything they can about this women, saying, “I’m going to make a movie about her. I’m going to find out what her real name is, who she was and is, everything I can find out about her, because something in her face, something in the way she looks and moves is serious, is interesting. And I’m going to just tell you all about it.”

Cheryl’s journey to create a film about Richards is framed as a film within a film. As the project takes off, the scenes of Cheryl and Tamara’s lives in the video store begin to be interspersed with video-cam recordings of Cheryl speaking to the camera as she explains her process as a filmmaker, along with her interviews with family members, archivists, and historians. This creates a layered, fragmented sense of “reality” cut between moments of commentary and reflection, which establishes a sense of discovery for the viewer, who is pulled along with Cheryl’s own discoveries, hurdles, and dead ends.

The film’s tension is held in Dunye’s quest to uncover the past. Dunye used an extensive amount of archival footage and photographs that serve as points of discovery throughout the film, which she originally tried to source through the Lesbian Herstory Archive and the Library of Congress.

“While the Lesbian Herstory Archive was filled with juicy material from African American lesbian life, including the Ira Jeffries archive (she appears in the film), it had no material on African American women in Hollywood. The Library of Congress, on the other hand, had some material from African American women in Hollywood, but none on African American lesbians. And as those resources were beyond my budget at the time, I decided to stage and construct the specific photos that I needed for the film, and did that in collaboration with Zoe [Leonard].”

Frustrated by the lack of formal scholarship and archived materials, Dunye conscripted the queer, New York-based artist and photographer Zoe Leonard to help create a “false” archive for the film. Leonard began her career as an active voice in AIDS advocacy and queer politics in New York in the 1980s and 1990s, becoming known for her 1992 treatise, I want a president, and 1995 installation piece Strange Fruit. Dunye and Leonard worked together to conceive of an archive for Richards, one that would double as a visual representation of this knowledge gap. Leonard then produced photographs and newsreels shot in black and white, with dated cameras and techniques. As Matt Richardson notes in his book Out Stories Have Never Been Told: Preliminary Thoughts on Black Lesbian Cultural Production as Historiography in The Watermelon Woman: “the viewer does not know whether these snapshots of black life from the 1930s and 1940s are of real people, thereby challenging the division between fact and fiction, past and present.” Since the film’s release, the archive has become recognized as a work of importance in itself, The Fae Richards Photo Archive, 1993-96.

In her same essay, Venus in Two Acts, Hartman coined the concept of critical fabulation, a style of creative semi-nonfiction that brings the suppressed voices of the past to the surface by means of hard research and scattered facts, but which includes aspects of fiction due to the scarcity of archived information. How do we confront the lack of such individuals’ stories? Hartman references scholar Michel de Certeau’s proposition for two methods to include such stories in archives: “one is attending to and recruiting the past for the sake of the living, establishing who we are in relation to who we have been; and the second entails interrogating the production of our knowledge about the past.” If the past proves incomplete due to lack of documentation, we must interrogate the means of documentation, and imagine alternative narratives. The Watermelon Woman suggests that there is space within art and archiving practice to imagine the kinds of stories that Hartman claims are perhaps the only available form of compensation. Fiction can inform our narratives just as much as proven fact. It also has the ability to make coherent what has been lost or misunderstood, to reframe the gaps in written history, to play with and reimagine that history, and to attempt to, in some ways, replace it.